Poetry

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to navigationJump to search This article is about the art form. For other uses, see Poetry (disambiguation). "Love poem" redirects here. For the EP, see Love Poem (EP). For the IU song, see Love Poem (song). Poetry (derived from the Greek poiesis, "making") is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic[1][2][3] qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, a prosaic ostensible meaning. Poetry has a long and varied history, evolving differentially across the globe. It dates back at least to prehistoric times with hunting poetry in Africa, and to panegyric and elegiac court poetry of the empires of the Nile, Niger, and Volta River valleys.[4] Some of the earliest written poetry in Africa occurs among the Pyramid Texts written during the 25th century BCE. The earliest surviving Western Asian epic poetry, the Epic of Gilgamesh, was written in Sumerian. Early poems in the Eurasian continent evolved from folk songs such as the Chinese Shijing, as well as religious hymns (the Sanskrit Rigveda, the Zoroastrian Gathas, the Hurrian songs, and the Hebrew Psalms); or from a need to retell oral epics, as with Egyptian The Story of Sinuhe, the Indian epic poetry, and the Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey. Ancient Greek attempts to define poetry, such as Aristotle's Poetics, focused on the uses of speech in rhetoric, drama, song, and comedy. Later attempts concentrated on features such as repetition, verse form, and rhyme, and emphasized the aesthetics which distinguish poetry from more objectively-informative prosaic writing. Poetry uses forms and conventions to suggest differential interpretations of words, or to evoke emotive responses. Devices such as assonance, alliteration, onomatopoeia, and rhythm may convey musical or incantatory effects. The use of ambiguity, symbolism, irony, and other stylistic elements of poetic diction often leaves a poem open to multiple interpretations. Similarly, figures of speech such as metaphor, simile, and metonymy[5] establish a resonance between otherwise disparate images—a layering of meanings, forming connections previously not perceived. Kindred forms of resonance may exist, between individual verses, in their patterns of rhyme or rhythm. Some poetry types are unique to particular cultures and genres and respond to characteristics of the language in which the poet writes. Readers accustomed to identifying poetry with Dante, Goethe, Mickiewicz, or Rumi may think of it as written in lines based on rhyme and regular meter. There are, however, traditions, such as Biblical poetry, that use other means to create rhythm and euphony. Much modern poetry reflects a critique of poetic tradition, [6] testing the principle of euphony itself or altogether forgoing rhyme or set rhythm.[7][8] In an increasingly globalized world, poets often adapt forms, styles, and techniques from diverse cultures and languages. Poets have contributed to the evolution of the linguistic, expressive, and utilitarian qualities of their languages. A Western cultural tradition (extending at least from Homer to Rilke) associates the production of poetry with inspiration – often by a Muse (either classical or contemporary).

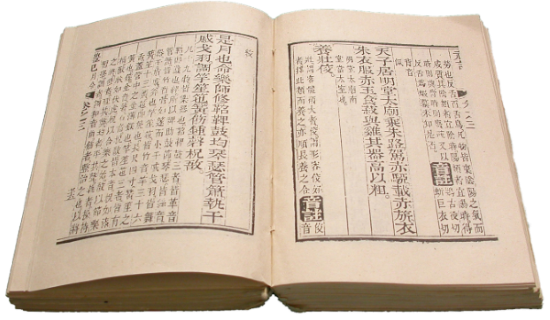

Some scholars believe that the art of poetry may predate literacy and developed from folk epics and other oral genres. [9][10] Others, however, suggest that poetry did not necessarily predate writing.[11] The oldest surviving epic poem, the Epic of Gilgamesh, dates from the 3rd millennium BCE in Sumer (in Mesopotamia, present-day Iraq), and was written in cuneiform script on clay tablets and, later, on papyrus.[12] The Istanbul tablet #2461, dating to c. 2000 BCE, describes an annual rite in which the king symbolically married and mated with the goddess Inanna to ensure fertility and prosperity; some have labelled it the world's oldest love poem.[13][14] An example of Egyptian epic poetry is The Story of Sinuhe (c. 1800 BCE). Other ancient epics includes the Greek Iliad and the Odyssey; the Persian Avestan books (the Yasna); the Roman national epic, Virgil's Aeneid (written between 29 and 19 BCE); and the Indian epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Epic poetry appears to have been composed in poetic form as an aid to memorization and oral transmission in ancient societies.[11][15] Other forms of poetry, including such ancient collections of religious hymns as the Indian Sanscrit-language Rigveda, the Avestan Gathas, the Hurrian songs, and the Hebrew Psalms, possibly developed directly from folk songs. The earliest entries in the oldest extant collection of Chinese poetry, the Classic of Poetry (Shijing), were initially lyrics.[16] The Shijing, with its collection of poems and folk songs, was heavily valued by the philosopher Confucius and is considered to be one of the official Confucian classics. His remarks on the subject have become an invaluable source in ancient music theory.[17] The efforts of ancient thinkers to determine what makes poetry distinctive as a form, and what distinguishes good poetry from bad, resulted in "poetics"—the study of the aesthetics of poetry.[18] Some ancient societies, such as China's through the Shijing, developed canons of poetic works that had ritual as well as aesthetic importance.[19] More recently, thinkers have struggled to find a definition that could encompass formal differences as great as those between Chaucer's Canterbury Tales and Matsuo Bashō's Oku no Hosomichi, as well as differences in content spanning Tanakh religious poetry, love poetry, and rap...